Nicosia: A city divided

I was five years old when the Berlin Wall fell, and in the years since I’ve seen bits of the wall all over Europe: outside the European parliament in Brussels, in a park in Riga, opposite Hoxha’s Pyramid in Tirana, and outside the Imperial War Museum here in London. The wall lives on both physically and psychologically – Germans still talk of the Mauer im Kopf, the ‘wall in the head’ – but I came into this world too late to experience what the city was actually like with the wall running through it. There is, however, a city in Europe that is still divided down the middle, the legacy of a conflict that began over 50 years ago.

Nicosia is the capital of two countries: the Republic of Cyprus, a majority Greek-speaking EU member state that claims sovereignty over the whole of the island of Cyprus, and the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, a pariah state whose legitimacy is recognised only by Turkey. The Turkish army invaded the island in 1974 after a coup staged by Greek Cypriot nationalists who wanted to incorporate Cyprus into Greece, a coup that came on the back of 11 years of violence between the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities. The Turkish army occupied around 40% of the island before a ceasefire was declared, and Cyprus has been split down the middle by a UN buffer zone ever since, a line that slices right through the centre of Nicosia.

We drove down to Nicosia from Girne, on the north coast, and although it was September the city was baking hot, a heavy inland heat somewhere in the high 30s. The streets of north Nicosia were in a state of what you might call elegant decay, a warren of cobbled streets and crumbling ochre buildings, many still pitted with bullet holes from 1974. There was a distinctly Eastern feel to the old city, which, along with the stifling heat, served as a reminder that Cyprus is geographically in the Middle East; Nicosia is closer to Beirut and Damascus than it is to Ankara or Athens.

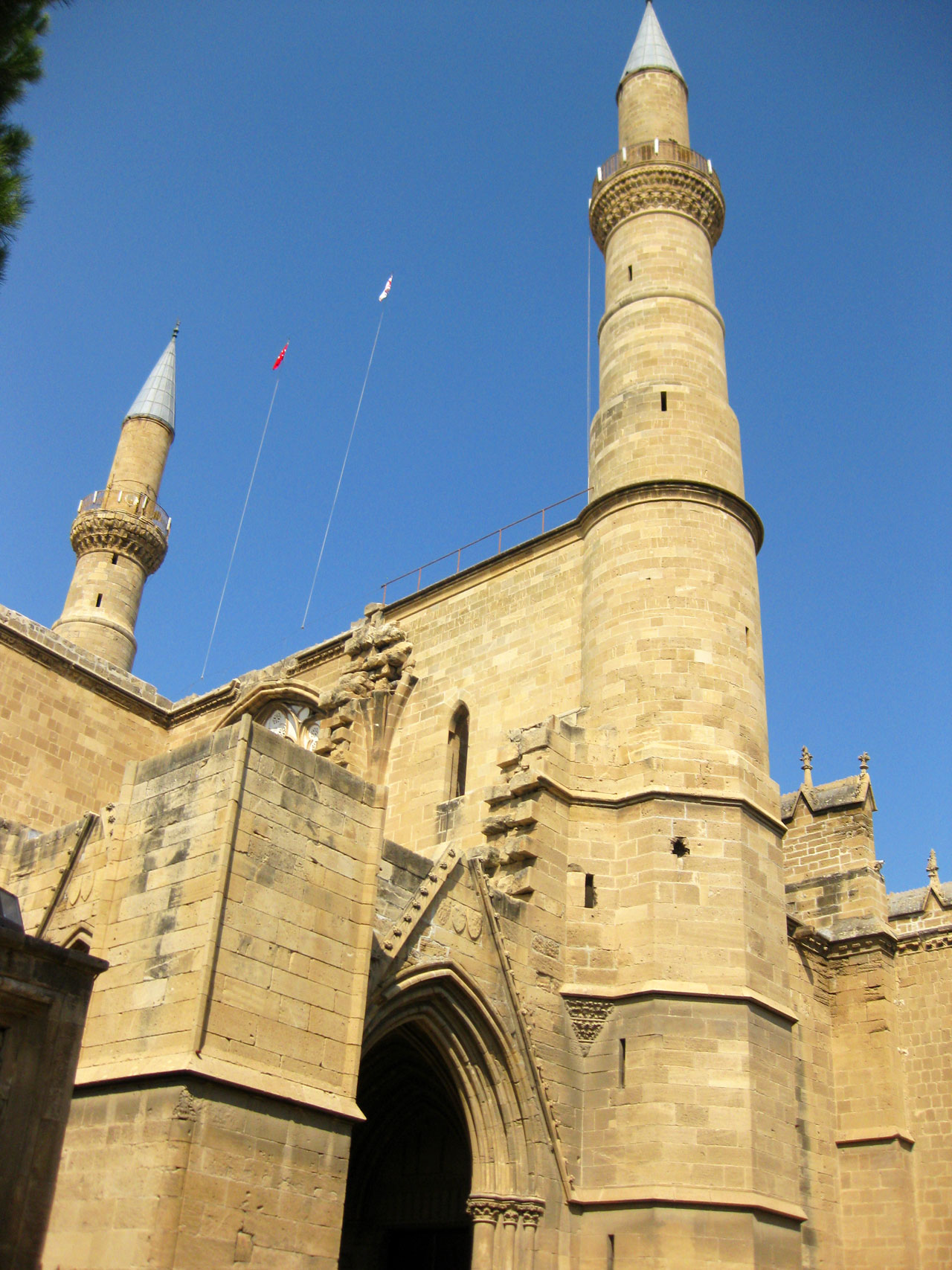

Wandering along a bazaar-like street flanked by stalls selling assorted goods and tourist tat, we spied north Nicosia’s most distinctive landmark, the twin minarets of the Selimiye mosque. This remarkable structure looks like a Christian cathedral with two minarets bolted on top, and that’s essentially what it is; the building, built by the French in the 13th century, was originally the Cathédrale Sainte Sophie, until the Ottoman Turks invaded Cyprus in 1570 and turned it into a mosque. It was the first mosque I’d ever visited, and the inside of the building felt slightly surreal to me; the layout, the windows and the vaulted ceiling were just like what you would find in any other European cathedral, which made the Arabic writing on the walls seem utterly incongruous.

The streets around the mosque were pleasant to wander along, with the narrow alleyways providing some shade from the relentless midday sun, and I succumbed to the temptation to go ‘full tourist’ at an indoor market, purchasing a decidedly inauthentic fez with a Turkish flag emblazoned on the front. The market was right next to the the UN buffer zone, which is demarcated by two parallel walls topped with coils of barbed wire. In places there are abandoned houses between the walls, stranded in no-man’s land, and it’s here that the war damage is most visible, the buildings riddled with bullet holes and damage from shrapnel. As I wandered down an alleyway alongside the wall to have a closer look I heard a shout from behind me, and turned to find an angry soldier barking something at me in Turkish, which I quickly realised was a warning that I was walking into the buffer zone.

Although it’s easy to cross between the two halves of the city these days we decided to give south Nicosia a miss, as we’d been told that it was a lot more westernised and less interesting than the north. We had lunch at a restaurant within the courtyard of the Büyük Han, an old Ottoman caravanserai centred around a little domed mosque, before carrying on along the edge of the buffer zone towards the city walls, emerging at a dried up park overlooked by a UN watchtower. If you look at a map of old Nicosia you’ll find that the city walls are very geometrically pleasing when viewed from above, consisting of a perfect circle and eleven arrow-shaped bastions, built by the Venetians in a vain attempt to keep the Turks out.

I liked Nicosia a lot, and my initial comparison to pre-1989 Berlin is perhaps not entirely accurate; although the physical and political barrier between the two halves of Nicosia still exists, the border is open and Cypriots from both sides are allowed to pass back and forth freely. It’s nevertheless a fascinating place, and the city’s long history of domination by foreign powers puts the current political situation in Cyprus into some context; over the years the Byzantines, the Franks, the Venetians and the British have all held sway here, and Turkish occupation is certainly nothing new. It’s also a place where this turbulent history is still very visible, from the cathedral-turned-mosque and the Venetian fortifications all the way through to the barbed wire and guard towers that divide the city today.