Gdańsk: The indestructible city

I rubbed the sleep from my bleary eyes as our taxi driver, unfeasibly chirpy for six o’clock on a Monday morning, fired yet more questions at us.

“What about the basilica, did you go up to the top of the tower?”

“Er, no, we didn’t… we saw it, but we didn’t go up to the top.”

“You didn’t? Ah, that’s a shame. Very nice views from the top. There is a place called Oliwa, 10 kilometres from the city centre, a very beautiful cathedral, maybe you visited here?”

I glanced sheepishly across at Polly.

“No, we didn’t make it to Oliwa actually…”

I tailed off, feeling a little chastened, but there was no disappointment in his reply, just a sort of childish enthusiasm.

“Ah, well… You have plenty of reasons to come back then!”

He had a point. We’d had a pretty busy three days in Gdańsk, yet it seemed like we’d barely scratched the surface of all the history and drama bound up in the fabric of this resilient old city.

The historic centre of Gdańsk had been the first surprise, an eloquent rejoinder to all those preconceptions of Poland as a drab and dour place; instead we found ourselves walking cobbled streets bounded by tall, gabled facades, reminiscent of both the Flemish flair of Bruges and the Hanseatic grandeur of Riga. The word ‘facade’ is rather apposite, however, as all is not what is seems in Gdańsk. Although it is now a thoroughly Polish city, Gdańsk has a long German history, dating all the way back to 1308 when the city was captured by the Teutonic Knights, and it was a Prussian stronghold for many years. After the First World War it was removed from German control and designated as the Free City of Danzig, one of the many territorial adjustments that fomented such resentment in Germany between the wars. During the Second World War Gdańsk was near flattened by heavy Allied and Soviet bombing, and after the collapse of the Nazi regime the city’s remaining German population mostly fled. In the subsequent Polish reconstruction of the city all German influences were controversially airbrushed out, replaced by Italian, French and Flemish flourishes.

Although this act of cultural revisionism continues to rankle with many Germans, it is perhaps understandable that the city was ‘de-Germanised’ given the appalling things that happened in Poland under the Nazis. Indeed it was just to the north of Gdańsk, on 1 September 1939, that the German battleship Schleswig-Holstein opened fire on the Polish naval base at Westerplatte, the first volley in what was to become the Second World War. Westerplatte is located on a peninsula where the river Vistula spills into the Baltic Sea, and we took a trip up there on a pretend pirate ship called the Czerna Perla, the ‘Black Pearl’. It was perhaps not the best way to afford this site the solemn respect it deserves, but there was a convivial atmosphere on board, the bowels of the ship filled with Polish families knocking back beer and vodka shots at 10 o’clock in the morning.

A hilltop memorial now stands at Westerplatte, a typically Soviet-style monolith hewn from stone, and there is still a lingering bleakness to the surrounding area. As we followed the river north from Gdańsk the elegant brick facades of the city centre were replaced by steel and iron, the great hulking shipyards and slag heaps strung out alongside the water in an angular cacophony of green cranes, rusty red warehouses and flashing sparks. Our little ship was dwarfed by huge vessels lying beached in dry dock or loading up with cargo, their hulls sheer like cliffs and their crew like tiny ants up on deck.

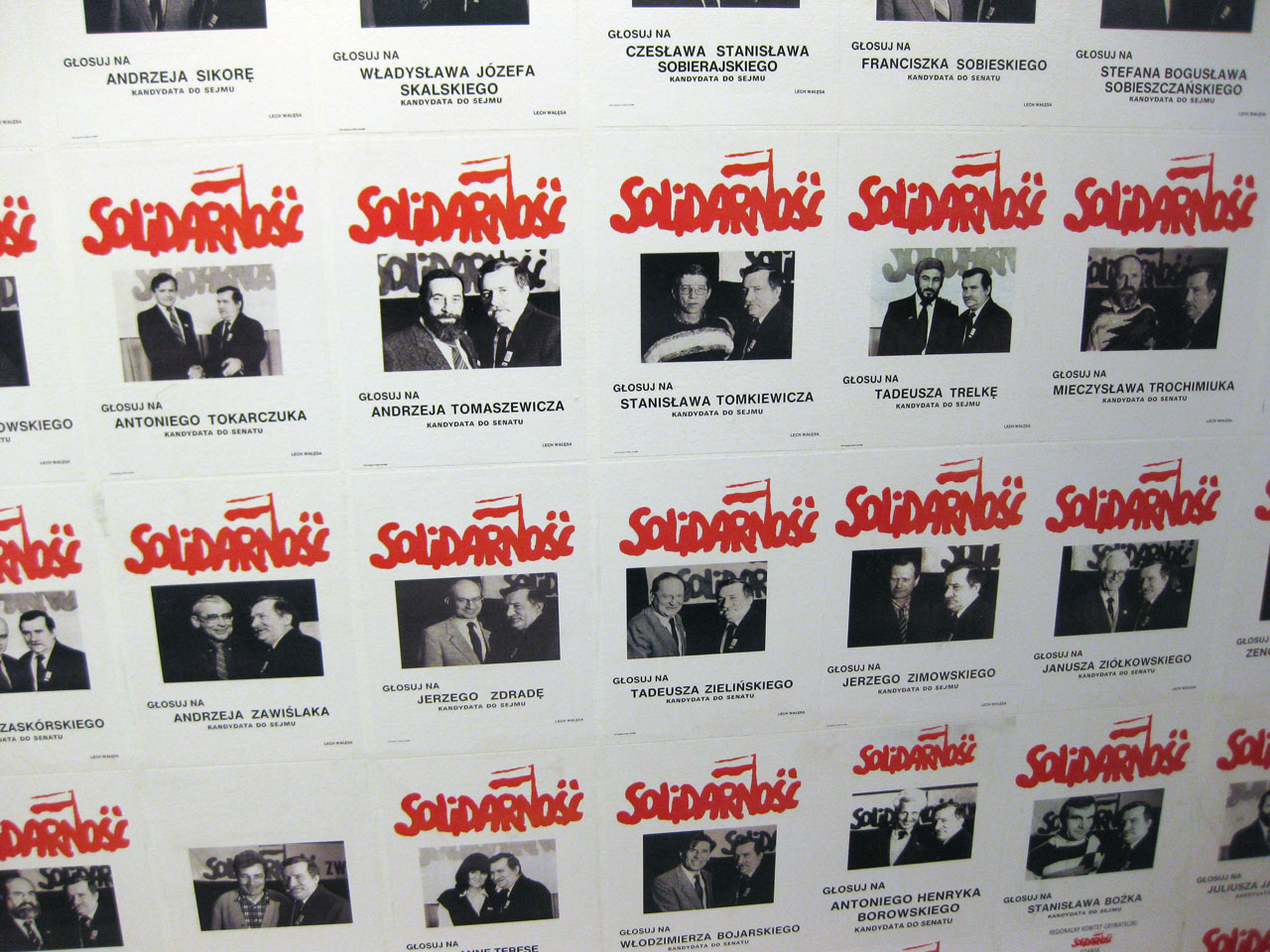

These sprawling shipyards are intimately connected with that other great rupture in the historical fabric of the last century, the fall of the Iron Curtain. In 1980 the old Lenin Shipyard was the scene of the strike that gave birth to Solidarność (Solidarity), the independent trade union that landed the first mortal blow on the ailing communist Goliath. Led by the charismatic Lech Wałęsa, the striking workers posted a list of 21 demands, chief among which was the right to join trade unions that weren’t affiliated to the Communist Party. The First Secretary of the Polish People’s Republic, a Soviet stooge named Wojciech Jaruzelski, came down hard on the nascent Solidarity movement, declaring martial law in December 1981 and imprisoning Wałęsa. The momentum was on the side of the people, however, and the Party’s grip on power gradually loosened over the course of the decade, culminating in the democratic elections of 1989, when the communists were booted out.

This is, of course, a very condensed account of one of the most important political movements in recent European history. For a more detailed re-telling of the story we visited the European Solidarity Centre, a huge new museum that now stands by gate number 2 of the old shipyard. This gate is where the 21 demands were first put on display, and it became a symbol of the protests that convulsed Poland in the early ’80s. The museum itself is a cavernous box-like structure coated in rusted sheet metal, with a huge amount of information on display; too much to absorb in one visit, to be honest, but I still left feeling like I’d learnt a huge amount. I was struck by a certain irony in the fact that organised labour played such an important role in bringing down the rotten communist edifice; a warning to self-proclaimed socialist politicians everywhere, perhaps, of what can happen if you lose touch with your working class roots.

In recent years the shipbuilding industry here has undergone something of a recovery, which would have seemed improbable just a decade ago, but there are still plenty of derelict yards and abandoned cranes. As with post-industrial cities the world over, new uses have been found for the warehouses and workshops, and just a short walk from the Solidarity Centre we came across an area more reminiscent of Hackney Wick than the golden age of socialism, where a pop-up bar, art gallery and event space were clustered around a weed-encrusted concrete yard. The entertainment was a little different to what you might find in East London though, with a bodybuilding competition taking place the afternoon we were there, and posters advertising ‘Solidarity of Salsa’, which seemed an ever so slightly inappropriate co-opting of Gdańsk’s recent past.

I had expected the grit and the grime and the post-industrial decay, but what really surprised me about Gdańsk was how picturesque the place was. Although perhaps not as famous as the cranes that loom over the old Lenin Shipyard, the 15th century version that stands next to the Motława river is another symbol of the city. This strange and wonderful building has the most bizarre dimensions, quite unlike anything I’d seen before. At one time it was the biggest crane in Europe, perhaps the world, and was used to load up ships with cargo weighing up to four tonnes.

The area around the Crane was also full of places to enjoy a drink, and we were surprised by just how good a lot of the food was, completely dispelling the outdated notions I had about Polish cuisine being a turgid mass of dumplings and cabbage and despair. Our most memorable evening was spent back on the Black Pearl, which drops anchor next to the old town at the end of each day and serves as a floating bar. We both ordered a glass of Goldwasser, a type of local vodka flecked with gold leaf, and enjoyed a couple of hours of people-watching. As the bar gradually filled, a musician with a mullet started belting out a mixture of sea shanties and old Polish pop songs, and a table of local lads, all dressed in sailing gear, started bellowing the songs along with him, banging bottles of Tyskie together jubilantly at the end of each song and guzzling them down in toast after noisy toast. It seemed to sum up Gdańsk perfectly: a place that can take a lot of punishment, and yet still come out the other end with a smile on its face.