Climate Change & Travel Part 2: The lies we tell ourselves

Unless you cling to the idea that man-made climate change is a hoax designed to line the pockets of devious scientists, or a natural fluctuation in the earth’s temperature, or whatever diversionary story is currently flavour of the month amongst climate change deniers and their corporate funders, it should be clear that our warming planet presents a clear and present danger to our civilisation, and to the future of travel as we know it.

The trouble is, as I pointed out in my previous post, most of us know this already, and yet we steadfastly refuse to engage with the issue. The biggest single contribution most travellers make to climate change is their aircraft emissions, and yet it also tends to be the vice we’re most reluctant to sacrifice. We ignore this whopping great elephant in the room, or we look for excuses as to why we can’t change our habits. These excuses should be familiar to any self-proclaimed environmentalist who continues to fly frequently: we protest that one person giving up flying is not going to make any difference to such a big problem; we point out that aircraft emissions only make up a small percentage of total global CO2 emissions (2% is the oft-quoted figure in the travel industry, although in the UK it’s more like 6%); we cross our fingers and hope that technology will save the day, with renewable fuels or more fuel-efficient planes; or we try and convince ourselves that the benefits that tourism brings to places like the Caribbean or the Maldives somehow outweigh the damage done by climate change.

I’m one of those people. I care greatly about the planet – or at least I tell myself I do – and I try to reduce my carbon footprint where I can, but I continue to fly once or twice a year. I feel guilty sometimes, of course, but not guilty enough to change my habits. And if those of us who are reasonably clued up on the environment, and who care about climate change, are unwilling to cut back on air travel, then what hope is there of winning over those who are oblivious or indifferent to the harmful effects of flying?

Part of the problem is the feeling of helplessness and insignificance that can overcome us when confronted with the scale of the challenge. We look at the world around us and it just seems so unlikely that the necessary shifts in attitudes and behaviour are going to come about, be it through individual actions, decisive measures from our politicians or a more responsible approach from business. If we’re being honest, many of us think: Why me? If other people are going to carry on flying, what’s the point in depriving myself of that pleasure? Life is short, after all. And so we absolve ourselves of any personal obligation to act, and we shift the responsibility on to the politicians and big business.

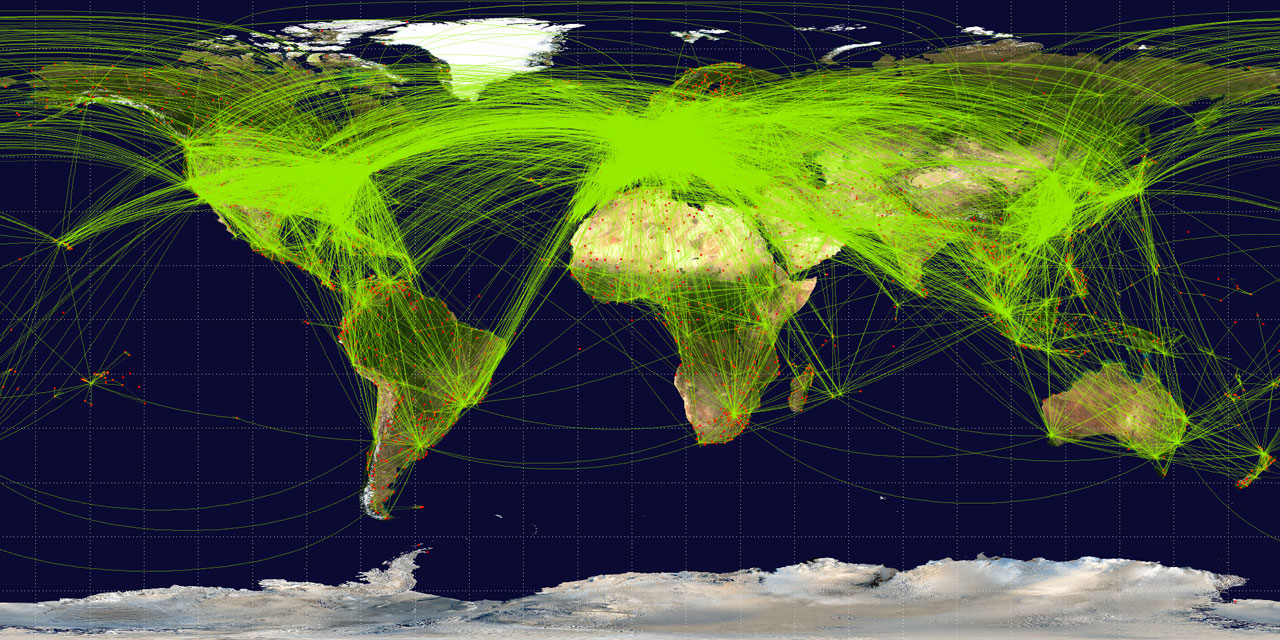

Of course, no politician is ever likely to win an election on a platform of banning air travel, or restricting the right to an overseas holiday. If anything the political debate is moving in the opposite direction, with the western orthodoxies of perpetual economic growth and consumerism taking hold on a global scale. In the UK, the debate around aviation is not about how to restrict it, but where best to expand our airport capacity to allow more flights to criss-cross our skies, with little more than lip service paid to the mounting evidence that current levels of aviation are environmentally unsustainable. It strikes me as utter madness, and I say that as someone who works in the travel industry.

“The world’s major cities are planning to build more than 50 runways by 2036 to allow for an extra 1bn passenger journeys a year. By contrast, our decision to build one additional runway has been dogged by years of indecisiveness. It is clear that Britain is at a crossroads. Either we choose to modernise our airport infrastructure or, inevitably, we get left behind.”

Michael Spencer, founding signatory of pro-airport expansion campaign Let Britain Fly

Meanwhile, in emerging economies such as China and India, a newly affluent middle class is demanding, quite understandably, the right to the same low-cost jet-setting holidays that we in the west take for granted. Global air traffic surged by 73% between 2003 – 2013, in spite of the economic downturn, and it’s predicted to double again by 2033. Budget airlines are springing up across the Asia-Pacific region to cater for demand, and who are we in the west to say “No, you can’t have what we had”?

“India…is amongst the fastest growing and currently the 9th largest aviation market handling 121 million domestic and 41 million international passengers… The studies suggest that by the year 2020, India is likely to become the 3rd largest aviation market handling 336 million domestic and 85 million international passengers with projected investment to the tune of US$ 120 billion.”

Indian Ministry of Civil Aviation press release, 26 March 2013

Nor can the travel industry be relied on to tackle its contribution to climate change in a meaningful way. Although there are many individuals and organisations doing great work to make travel more responsible and sustainable, the fact remains that the bottom line will always be the priority for shareholders, and in most businesses this is seen through the prism of the short-term future, with little consideration for the long-term economic repercussions of climate change. This has been especially true over the last five or six years; for most travel companies, simply staying afloat in a market that has been violently disrupted by the internet and the economic downturn has trumped all other concerns.

Even where there is willing from CEOs, any company that relies on air travel to sustain its business model is going to find it difficult to take a principled stand on climate change. “We don’t want to put people off travelling altogether”, a manager of mine once told me when I tried to add a paragraph on aircraft emissions to a brochure, and to be fair he was right. That is the exact opposite of what I was employed to do.

Nevertheless, too many businesses have their heads in the sand, and deploy many of the same arguments that we use as individuals. It’s that same mentality of Why us? Why reduce our emissions if all it will achieve is to hand a commercial advantage to our competitors? There is also still a widespread perception that sustainability is a niche interest in the same vein as ‘spa holidays’ or ‘adventure travel’, rather than something that should be hardwired into the DNA of any company that expects its business model to survive the next twenty years. Too many people in the industry think that as long as they sell a few hotels with turtle conservation programmes, or furniture made of sustainably harvested wood, they are basically doing their bit for the environment.

“Energy costs too high to travel; locations too unsafe to visit because of social upheaval; water no longer available to drink. All these issues will shape the future success of tourism companies.”

The Travel Foundation, Survival of the fittest: Sustainable tourism means business

And one thing you can be sure of is that, if individual and corporate behaviour remain unchanged until the point where climate change becomes impossible to ignore, the government action that will eventually result is likely to be heavy-handed and ruinous for much of the travel industry. The blunt instrument most governments are likely to reach for is tax, and future carbon taxes are likely to be far more punitive than anything on the statute books today. A continuing reliance on kerosene also means that the industry is exposed to volatility in the price of oil, with many oil-producing countries located in the very regions that are most vulnerable to the disruptive effects of climate change. There is a real possibility that long haul travel will once again become the sole preserve of the super rich, as the cost of flying becomes prohibitively expensive.

So if our governments remain wedded to an economic model founded on unsustainable growth and fossil fuel consumption, and businesses can’t be relied on to act in their own long term interests, then what hope is there? If we’ve already locked in 4°C of warming by the time governments are forced into action, then all of the devastating effects I’ve described will be reshaping the travel landscape, and the majority of us will face a future in which we can no longer afford the holidays that we once took for granted.

This is why I’ve come back around to the conclusion that the onus is on us as individuals; if we want things to change, we have to stop making excuses and play our part in mapping out an alternative future. In the final post in this series, I will look at what we can do as travellers to give ourselves a fighting chance in the difficult decades that lay ahead.