Tbilisi: The city on the edge of Europe

Where does Europe end and Asia begin? If you look at a map, the idea that Europe and Asia are separate continents doesn’t really make sense. It’s always been a hazily defined border, shifting back and forth over the centuries, perhaps reflecting the fact that Europe is more of an idea than a clearly defined landmass. The republic of Georgia sits squarely within the intercontinental grey area, often considered part of geographical Asia, but culturally part of Europe.

It was perhaps inevitable that ideas of European identity were on my mind when we arrived in Tbilisi, given that several million of my fellow Britons had recently voted to leave the European Union. One of the first buildings of note that we came across was the old Parliament building, and I found it striking that outside flew two flags: the white and red of Georgia, and the blue and gold of the European Union. Georgia signed an Association Agreement with the EU in 2013, and still harbours ambitions to join the Union in spite of both Europe’s current travails and Georgia’s 2008 war with Russia, which was widely interpreted as a move to put the increasingly Western-facing government firmly in its place.

There was something quite poignant about seeing the EU flag flying everywhere in Tbilisi, the capital of a country that is still a long way from being accepted into the club, when that same flag had been so roundly rejected in the UK just a few months earlier. And I was initially a little surprised by just how European the city seemed, in spite of its geography; Tbilisi is further east than Baghdad or Damascus, and closer to Kabul than it is to Brussels. The frenetic main thoroughfare, Rustaveli Avenue, was lined by elegantly European architecture built by the Russians in the 19th century, and many of the buildings housed boutiques flogging high end Western brands. We walked past buskers playing tunes by Radiohead, and teenagers pouting into their iPhone cameras.

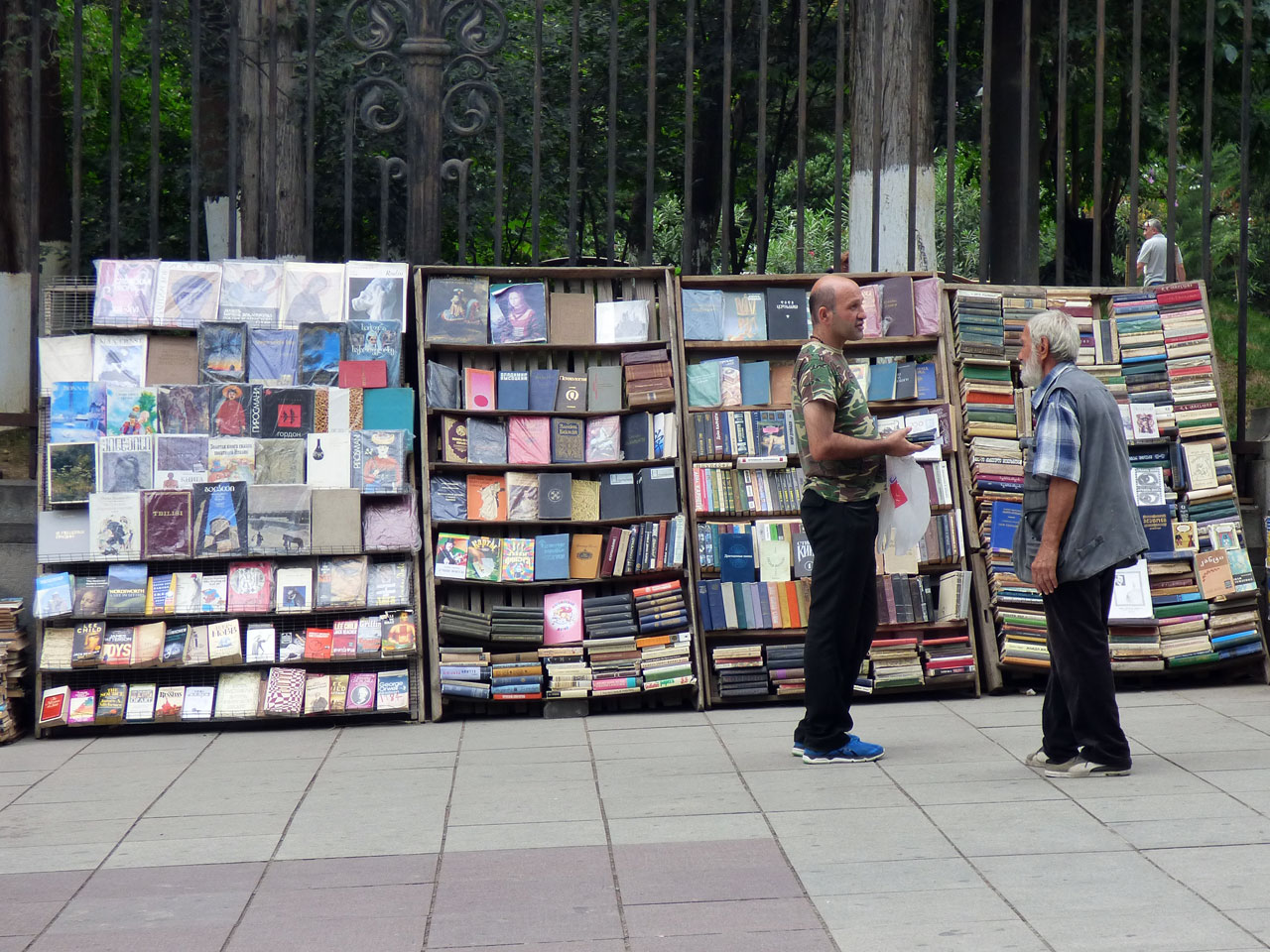

But first impressions can be superficial, and Tbilisi is the guardian of a complicated history that places the city somewhere in between two continents, neither completely European nor completely Asian. At the bottom of Rustaveli Avenue a man was selling faded old communist tomes; nearby, an old woman tried to scrape a living by charging people to be weighed on her scales. Both scenes were familiar Soviet hangovers that we’d seen in Albania and Uzbekistan. We crossed the traffic-blighted street by way of a urine-scented underpass, which was filled with dingy little shops selling everything from sunglasses to religious icons. A sign at the entrance described it as an ‘underground retail zone’, but it was tawdry and a little sad, reminiscent of a provincial Asian market filled with cheap knock-off goods.

We emerged on the edge of Tbilisi’s Old Town, and suddenly we were in a different city. Intricate balconies overhung the narrow streets, some in a state of spectacular disrepair and others spilling over with dangling foliage. At the centre of it all was one of the Old Town’s best known (and newest) buildings, the clock tower of the Gabriadze puppet theatre. Built in a deliberately wonky and mismatched fashion, it seemed perfectly in keeping with the ramshackle nature of the surrounding streets.

Georgia is, by its own reckoning, one of the most religious countries on earth, with almost 90% of Georgians declaring themselves to be Christian in a recent survey. Tbilisi’s Old Town is home to several handsome old churches built in the distinctive Georgian style, with a pointed dome on top of a round tower. In the garden outside the 6th century Anchiskhati Basilica, Tbilisi’s oldest surviving church, we saw a man skinning a dead sheep hung from a tree, a scene that I can’t imagine encountering in many other European capitals these days. Tbilisi often seemed to embody Georgia as a whole, in the sense that it was both looking forwards, towards a more prosperous, westernised future, and at the same time remained rooted in a traditional, socially conservative way of life that is more typical of the East.

After a light lunch of beer and khinkali, a type of dumpling that appears on every Georgian menu, we came upon another striking juxtaposition of the old and the new, as we crossed the unabashedly modern Peace Bridge over the river Mtkvari. This bridge has been unfavourably compared to a sanitary towel on account of its unusual curved shape, and is one of several ostentatious new landmarks sprinkled around Tbilisi by the controversial former president, Mikhail Saakashvili. I actually thought it was one of the city’s more appealing modern structures, and from the middle of the bridge we had a great view of the Narikala Fortress, which sits on a ridge overlooking the city.

On the east bank of the river is the Rike Park, a pleasant green space decorated with yet more jarring space age architecture. The park is also the lower terminus for the cable car which runs from the Old Town up to the Narikala Fortress. We didn’t really fancy hiking up the hill in the midday sun, so we took the short ride up to the top, which cost less than £1 for the two of us. The history of the fortress is in many ways the history of the city; first established as a Persian stronghold in the 4th century, it was later captured and added to by the Arabs, the Turks and the Russians, as well as the Georgians themselves. There’s not actually that much of the structure left, but the views over the city were spectacular in the September sunshine, and we enjoyed a beer at a little bar at the top, under the steely gaze of the giant statue known as Kartlis Deda, ‘Mother Georgia’.

We spent our last morning in Tbilisi exploring the sprawling flea market that surrounds the ‘Dry Bridge’, so called because it straddles a road rather than the river. At first it just seemed like any other market in the former USSR, with men selling old army medals and Soviet memorabilia laid out on rugs, and babushkas trying to flog hideous-looking crockery and glassware, everything from decanters shaped like fish to vases adorned with Stalin’s face. But the stalls just seemed to go on and on, and the further in we went, the more bizarre it seemed to get. Leathery faced men who couldn’t secure a spot in the main market had their wares spread out on car bonnets, and were selling ancient cassette players, Thermos flasks, gramophones, bootleg prog rock records and microscopes that looked like they’d been swiped from a lab. Some stalls specialised in nasty-looking weapons – knives, axes, swords, knuckledusters – while others traded solely in old surgical implements and dentist’s tools, with row after row of scalpels, probes and pliers laid out, gleaming menacingly in the sun.

In the end the only thing we bought was an old Russian poster, and we wandered down the river back towards the Old Town. Just south of the bustling square known as the Meidan, we reached perhaps Tbilisi’s least European area, centred around the old sulphur baths of Abanotubani. These domed, sandy-coloured structures stand in the shadow of the Narikala Fortress, next to a row of houses with brightly hued balconies and the Jumah Mosque, its blue-tiled facade reminiscent of those we had seen further east on the old Silk Road, in the desert cities of Bukhara and Samarkand.

Tbilisi is often described as ‘Eurasian’, a crossroads between East and West, and it seems a sensible term for a city that defies easy categorisation. Here are encapsulated all the tensions and contrasts that define the fuzzy frontier between Europe and Asia – modernity versus tradition, Christianity versus Islam, Russia versus the West – but Tbilisi is also a place that makes the lines we draw across the Eurasian landmass seem arbitrary at best, and needlessly divisive at worst. Out here on the very easternmost fringes of Europe there are, perhaps, some lessons to be learnt for those of us at the opposite end of the continent.