Lagoons, llamas and the Salar de Uyuni

As the familiar opening bars rang out, Andrés turned to us and grinned.

"Música classic!"

It was day one of our three day tour from San Pedro de Atacama to the Salar de Uyuni, and six of us were crammed into a jeep bouncing along the Bolivian altiplano through a surreal landscape of mineral-rich lagoons and snow-capped volcanoes, to the sound of the Bee Gees' "How deep is your love?"

Our companions on this trip were a German couple, also on a lengthy sabbatical, and a pair of Brits on a mad-sounding holiday that was taking them from Tahiti to Brazil via Easter Island, Chile and Bolivia in the space of just three weeks. Ferrying us around was Andrés, a stocky, coca-chewing Bolivian with a seriously eclectic taste in music.

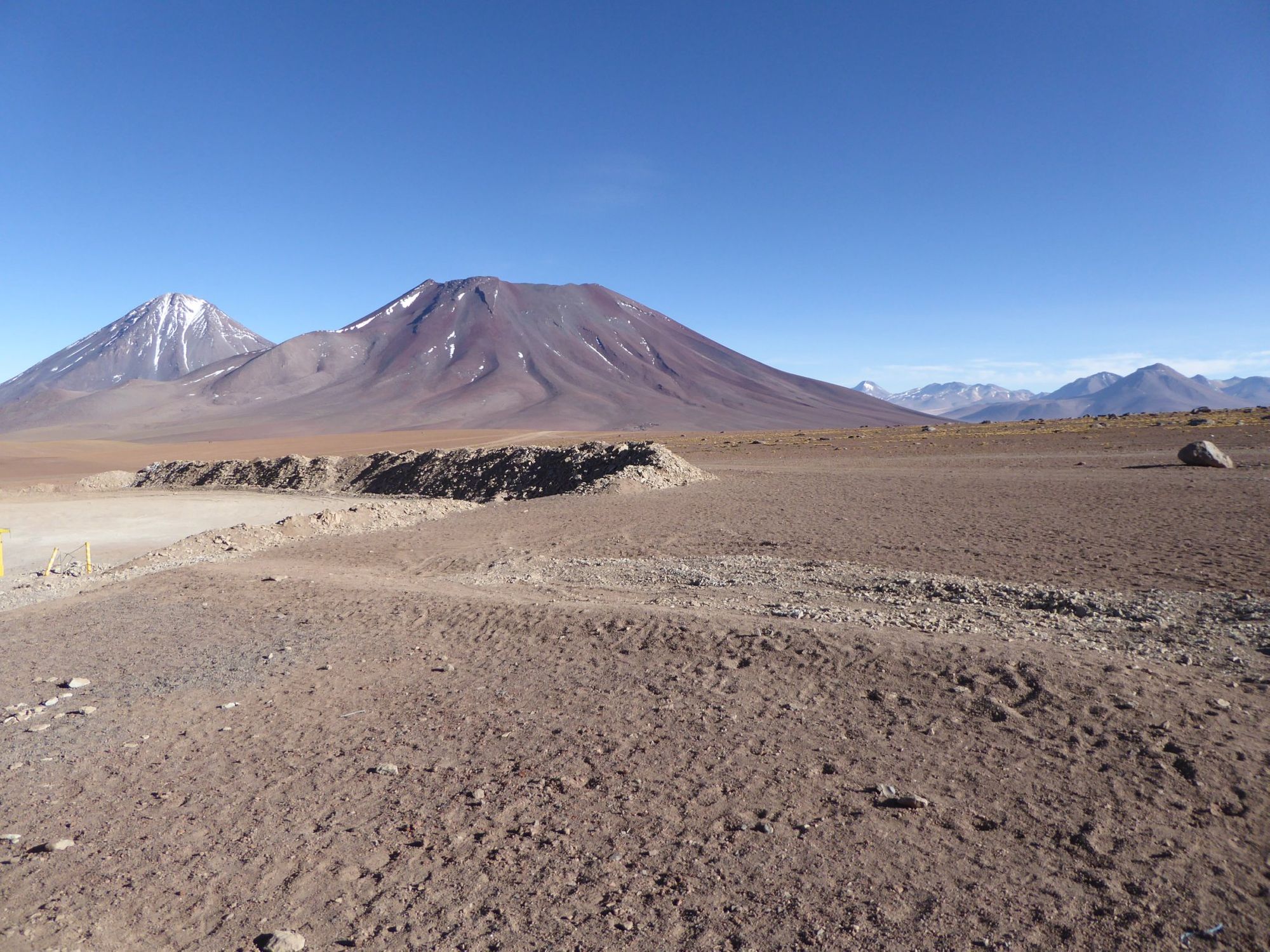

After a week exploring northwest Argentina and northern Chile I thought I'd seen the most spectacular scenery that the Andes had to offer, but Bolivia blew both of them out of the water within minutes of crossing the border. In the shadow of Licancabur volcano lay two startling lagoons: the Laguna Blanca, its mirror-like surface creamy with boron, and the Laguna Verde, a toxic brew of arsenic and sulphur.

The incredible variety of Bolivia's landscapes was almost too much to process on day one. At lunchtime we stopped at another lagoon, brilliant blue and filled with flamingos, where we had time to change into our swimwear and take a dip in the wonderfully warm hot springs, incongruously filled with fellow backpackers.

Later that afternoon we climbed to the highest point of the tour, a bubbling, spurting, sulphur-spewing landscape of geysers and fumaroles situated just shy of 5,000 metres above sea level. I coped much better at altitude this time round than on the bus from Argentina to Chile, something I attribute to the bottle of coca tea I was advised to bring with me by the owner of our hostel in San Pedro.

Coca leaves are a common sight in this part of South America, and we soon learnt to recognise their pungent smell too. The sale and consumption of coca is legal in the Andean countries, where it has been used both ritually and recreationally for thousands of years. Coca leaves contain the same active ingredient as cocaine, but at far lower concentrations, and the effect of chewing the leaves or making them into tea is that of a mild stimulant, comparable to coffee. Coca is also used as a natural remedy for altitude sickness, and although its efficacy hasn't been scientifically proven, it certainly seemed to work for me. Andrés gave us some leaves to chew, but they were pretty disgusting; the tea is far more palatable.

Our first day was drawing to a close, but Andrés still had one more incredible lagoon to show us, the Laguna Colorada. This huge body of water is tinged a deep blood red, and it's home to thousands upon thousands of flamingos. There are three different species here - Andean, Chilean and James's flamingos - and they feed on the algae that give the lagoon its unusual colour. When we arrived a ferocious wind was whipping up the desert dust, blasting us with sand as we struggled along the path to the viewpoint. In fact the wind was so strong and so full of grit that it did some serious damage to the zoom lens on my camera, which I still haven't been able to fix.

After a chilly night in a hostel built from the same cheap bricks as the favelas we'd seen in Brazil, we set off on the second day of our tour. Tracy Chapman and Elton John eased us into the day on Andrés's stereo, as we headed into a valley of weirdly-shaped rock formations. Andrés showed us rocks that were supposed to resemble the World Cup, a camel and, most bafflingly of all, an 'Italian city'. Try as I might, I couldn't quite see the resemblance.

We stopped off at another lagoon filled with flamingos, where a herd of llamas was drinking at the water's edge, and we enjoyed a picnic lunch in a rocky valley near a lagoon teeming with moorhens, ibis and geese.

In the afternoon the landscape subtly changed, becoming drier and more desert-like. We stopped at a scrubby, rocky clifftop that didn't seem like much, until we looked over the precipice and a great yawning canyon opened up beneath us, the sandy-coloured rocks divided by a greenish river.

Finally we arrived in Julaca, a bleak little village in the middle of nowhere, where shabby-looking houses squatted in varying states of collapse. We wandered around the abandoned railway station, littered with bits of old trains. A football pitch was scratched into the dust, a rusting goal at either end, and the main economic activity seemed to be charging tourists to use the rancid toilets. But perhaps the weirdest thing about Julaca was the shop selling bottles of craft beer. We bought two - one made with quinoa, the other with coca - and enjoyed a refreshing, surreal drink by the roadside before continuing on to our accommodation for the night, a hotel made of salt.

The hotel was a salty prelude to the climax of the tour: the Salar de Uyuni, the world's biggest salt flat. On day three we awoke bleary-eyed at 4 AM, loaded our bags onto the roof of the jeep and headed out into the pitch black night with Rammstein blasting out of the stereo, a wake-up call that even the Germans found to be a bit much.

As the horizon started to glow orange with the rising sun we got our first glimpse of the salt flat, a dream-like landscape of white, hexagonal crystals stretching as far as the eye could see. The jeep came to a stop and we got out onto the surprisingly hard, slightly crunchy surface, and stood rapt as the early morning sun bathed the salt flat in a purplish light.

Once the sun was fully up we got back in the jeep and drove to Isla Incahuasi, also known as Fish Island, a rocky outcrop covered in giant cacti. We climbed to the top of the island for a fantastic view over the salt flat, slightly out of breath from the altitude by the time we reached the summit.

After breakfast at Isla Incahuasi we headed out into an empty patch of the Salar to take the obligatory silly photos. The uniformity of the white surface stretching to the horizon means you can play with perspective and engineer some clever trompe l'oeil scenarios. Andrés was happy to help us, providing toy dinosaurs as props and lying face down on the salt to get the perfect angle for each shot.

After lunch at a little village on the edge of the salt flat we headed for our final destination, the town of Uyuni itself. I try to see the best in everywhere on my travels, but I think it's fair to say that Uyuni isn't the most attractive town in the world. The dusty, rubbish-strewn streets and ugly, half-finished brick buildings give the place a bit of a post-apocalyptic vibe in places, nowhere more so than at the town's main tourist attraction, the Train Cemetery.

Situated on the outskirts of Uyuni, just past a patch of waste ground heaped with rubbish, this collection of old steam engines and carriages has been left to rust in the desert, the wheels slowly sinking into the dust. After three days of travelling through some of the most surreal landscapes I've ever laid my eyes upon, it seemed a fitting place for our tour to reach the end of the line.