La Palma: Fire and water

La Palma, one of the lesser known Canary Islands, seems at first glance as if it must be a piece of the Caribbean that’s come loose, a wayward isle that has somehow drifted east across the Atlantic Ocean. There is barely a flat surface to be found on this lumpen volcanic rock, and the verdant coastal lowlands are carpeted with banana plantations. The high altitude of the central ridge means that moisture brought in off the Atlantic by northeasterly trade winds tends to get stuck, and as we set out to explore the south of the island a thick pillow of cloud sat glued to the peaks high above us.

The bananas which cover the landscape were introduced to the Canary Islands around the 15th century, and their cultivation constitutes the major industry on La Palma, subsidised by the Spanish government to allow it to compete with the mega-plantations of Central America. There are also plenty of reminders of another imported industry, in the shape of the many prickly pear cacti that dot the hillsides. If you look closely at these cacti, you can see that they’re covered in little white dots; these are cochineals, an insect that produces a bright red pigment known as carmine. Cochineal was a major a source of income on La Palma until the mid-19th century, when carmine was superseded by cheaper synthetic dyes and the bottom fell out of the market.

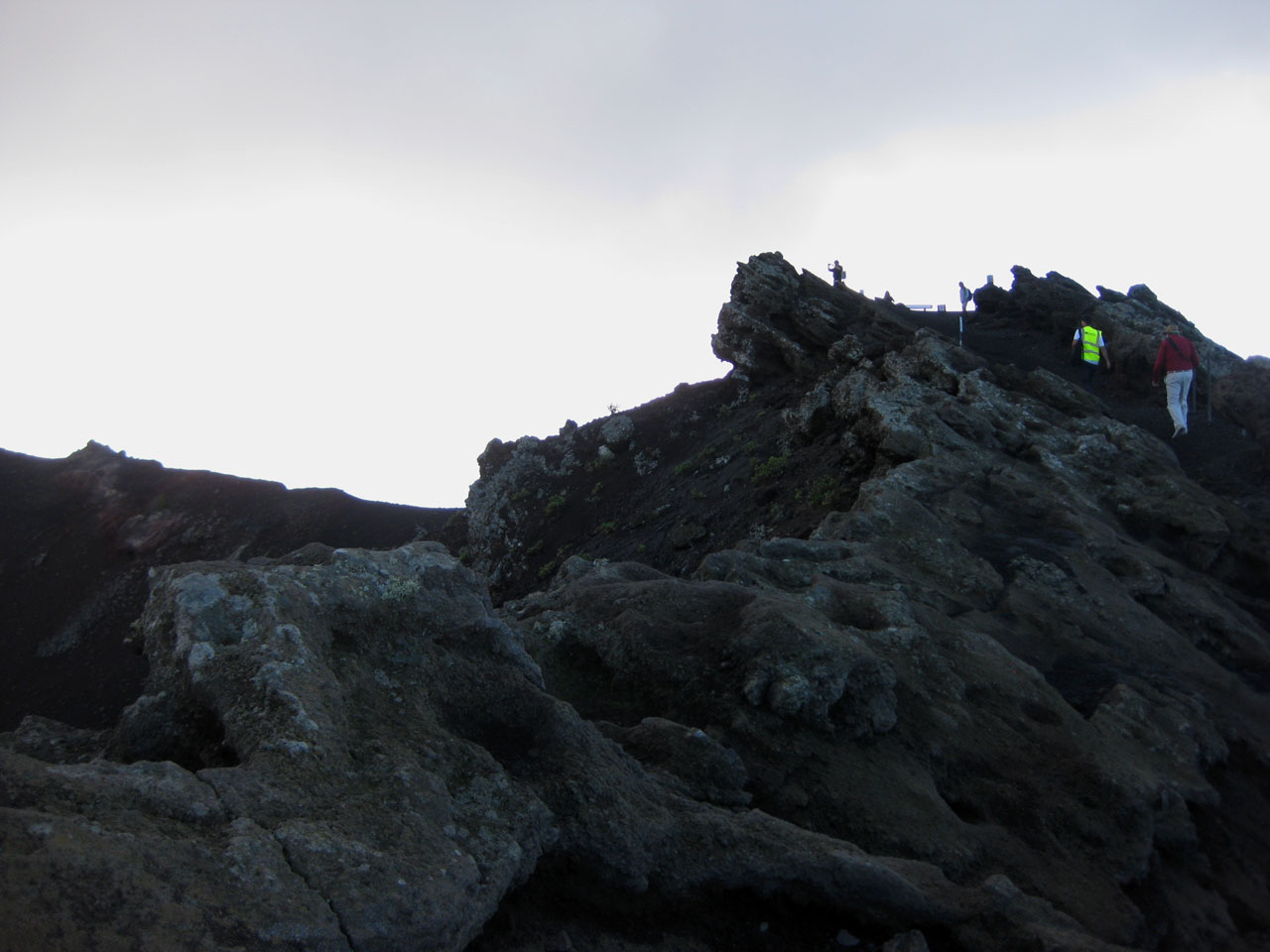

As we headed south the road climbed higher, and our surroundings changed from verdant plantations to a more severe landscape of charcoal black lava fields and scorched Canarian pine trees, which have evolved a degree of fire resistance thanks to the volcanic nature of the archipelago. La Palma is a relatively young island, formed around three to four million years ago, and the combination of a sub-tropical climate and the rich volcanic soil is what makes it so green and fertile. Just as the boiling bowels of the earth give life to La Palma, however, so they also pose a Damoclean threat of some fresh catastrophe that, if the more sensationalist reports are to be believed, could tear the whole island asunder. I contemplated this as I walked around the rim of the vast, black San Antonio crater, situated on the Cumbre Vieja ridge by the village of Fuencaliente. Our guide assured us that it was perfectly safe to be standing at the lip of the crater, which last erupted in 1677 and is now extinct; on the coastal plains below, however, we could see the cone of the Teneguía volcano, which erupted in 1971, killing a local fisherman. Apparently the barren black-brown surface around the crater, almost Martian in appearance, is still warm to the touch.

These signs of La Palma’s uncertain and unpredictable geological future were not the only allusions to impermanence. Human habitation of the island did not begin with the Spanish conquest in 1493, and it’s believed that the indigenous Guanche people had been living on La Palma since at least 1000 BC. No one is quite sure where they came from, although it is generally accepted that they were from somewhere in North Africa. The most likely explanation is that they were Berbers, from the area covered by modern day Mauritania, Morocco and Algeria; however, the discovery of mummified remains on La Palma has led others to posit that they may have originated in Egypt. While most traces of these indigenous inhabitants have disappeared, their influence lives on in some local crafts. We visited a pottery centre in a village of whitewashed houses and tranquil gardens, on a steep cobbled lane overhung with bursts of bougainvillea, and watched the master craftsmen at work using techniques and designs virtually unchanged since the days of the Guanches.

Despite the disappearance of La Palma’s original inhabitants, the island felt like more than just an outpost of mainland Spain. I loved the capital, Santa Cruz de la Palma, an incredibly photogenic collection of pastel-hued buildings in the sort of colonial style you’d expect to see in the Spanish Caribbean rather than the Canaries. Virtually the whole length of the main pedestrian street, Calle O’Daly, was lined by these sugary, sun-blushed facades, leading to the central Plaza de España, a triangular ensemble of beautiful whitewashed buildings, including the 16th century Iglesia Colegial del Divino Salvador.

I stopped for lunch on the seafront overlooking the black sand beach, at a little restaurant called ‘El Cuarto de Tula’, which also happens to be the name of a song by the Cuban group Buena Vista Social Club. It was another reminder of the historic links between La Palma and the Caribbean, which was the destination for many Canarians who emigrated during the colonial period. The Canaries were also the first stop for ships sailing back from the Americas laden with plundered treasure. This history is especially noticeable in the Spanish spoken on the Canary Islands, which bears a lot of similarities to Caribbean and Latin American Spanish. Alongside my jamón serrano and Manchego cheese sandwich, I had a side order of papas con garbanzada, a delicious dish consisting of potatoes in a garlic and chorizo sauce. The word papas for ‘potatoes’ originates from the Quechua language of the indigenous Andean people, and isn’t normally used in mainland Spain, but it’s widespread in the Canaries and Latin America.

My stay on La Palma was all too brief, but it certainly challenged many of my preconceptions about the Canary Islands. The mild winter climate, Europeanised culture and political stability compared to many other places at the same latitude have inevitably led to the Canaries being pigeonholed as a winter sun destination and not much else, but the archipelago is also a fascinating cultural crossroads. The many layers of history – African, European, Latin American and Caribbean – seem to overlap and push against each other, much like the tectonic plates whose explosive friction created these islands in the first place.